They tampered with the natural order of the world. “They” could be a wizard, a gene cult, the greys, the transhumanists, the Umbrella Corporation. It doesn’t matter anymore who it was. The important thing is that they created something unnatural, for a particular purpose. And their creation eventually outlived that purpose. But the world has found a new purpose for that creation.

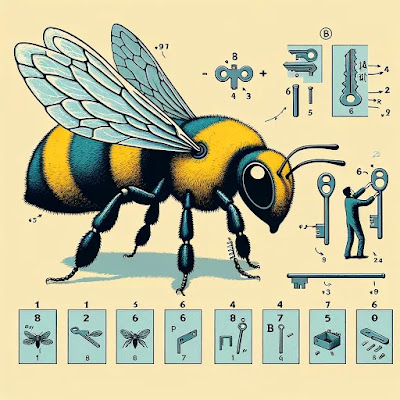

Keybees

The Prince Palisperous of the Court of Infinite Flowers bragged that no thief would ever pierce his floriferous vault and breathe in the scent of the Barbarous Orchid, most beautiful of all flowers. He offered vast riches for any who could prove him wrong. Again and again, the greedy, the foolish, and the brave tried their luck, with nothing to show for their efforts but a trail of adventurer corpses sprouting beautiful bouquets.

Uno the Humble Beekeeper was not an adventurer. He did not know how to fight monsters or disarm traps. But he did know everything there was to know about bees. And the bees knew everything there was to know about flowers.

Through selective breeding over seven decades, he cultivated the keybees, hives of bees each devoted to locating a particular kind of flower. A keybee could hone in on the faintest floral scent. No obstacle could stop a keybee for long, and if a keybee drone was killed, others would finish its work.

Keybee hives dedicated to finding the Barbarous Orchid sent waves of bees after the closely guarded flowers. Iterative testing of its defenses and accelerated breeding overseen by Uno led to a dexterous proboscis for picking locks and a sixth sense for avoiding monsters and traps. It took a long time, but the keybees were patient. The bees eventually pierced the vault, drank the nectar within, and returned to Uno, the first and only person to smell the nectar's scent. He died three days later, at the age of 99. He had never expressed any interest in the prince’s reward, and died content, with his life's work complete.

But Uno’s perfected keybees lived beyond their prescribed purpose. Hives propagated naturally, and the keybees retained their flower-seeking behavior. Feeding nectar from a particular flower (combined with the proper reagent) to a queen keybee from a new hive would produce the same flower-seeking effect. Uno’s successors found more pragmatic uses for the keybees.

Naturally, some applications were modeled closely on Uno’s original feat. Sneak a flower into the kingdom treasury and a keybee will guide you all the way in; that sort of thing. But there were other possibilities. Use a keybee to stress-test the security system. Sew a rare flower into your child’s cloak, and never worry about losing track of them again. Bury a cache of documents with a flowering plant that goes dormant in darkness; only those who know the flower type can locate it later with a keybee.

The Guardian Viper of Fearsome Banishment

The Plane of Endless Snakes was never a particularly popular destination for planar travelers. But apparently someone or something that once resided there was particularly interested in discouraging unwelcome visitors from trespassing in its sibilant halls.

So they created a special kind of guardian, the Greater Viper of Fearsome Banishment (or GVFB, as brevity is important when identifying and fleeing from venomous snakes). This creature not only delivered the deadly venom typical of many mundane snakes, but also the Banishment spell. Imagine the sight of an unfortunate interloper not only appearing back on their home plane, but writhing in pain from the snake's venom, as well; much more effective than the old “beware of snakes” signs.

These snakes outlived whatever entity created them, and in the snakely paradise of the Plane of Endless Snakes, they speciated into various forms, some less fearsome. Enterprising ophidiologists eventually discovered a strain of GVFBs that retained only a lesser strain of poison, but the full effect of the banishment spell (Guardian Vipers of Tolerable Banishment, or GVTBs, for short). While banishment is typically deployed coercively to, well, banish an interloper, nothing stops a planar traveler on a budget from directing the spell at themself for a quick emergency escape back to home turf. Uncorking an angry snake and intentionally inflicting a (nonlethal) bite on oneself is no one’s idea of a good time, but as an alterative to the cosmic terrors of the more hostile planes, it has much to recommend it.

Next Week: Even More Weird Second Lives of Useful Exotic Creatures