Last time: The World’s Largest Rewrite: Salvaging the Core Idea From a Megadungeon Disaster

#104: Sea Serpent (Lesser). Why “lesser”? There is no “greater” sea serpent in the OSE bestiary. Regardless, it is a chance to carve out a water area separate from the giant catfish's pond. One of the big problems with the original WLD, relative to megadungeons like Arden Vul or Thracia, is its flatness; most good megadungeons are three-dimensional, and defined as much by their depth as their breadth.

We won't worry too much about specifics just yet -- the diagram I posted at the end of the last post is for abstracted, relative positions. But lets assume the lower parts of this dungeon are flooded with seawater, and this was an Alcatraz-style island prison before it became an adventuring site. I like the idea that this part of the dungeon is a possible escape route, but made dangerous by sea creatures that have made their lairs here. The serpent is tough enough to dissuade most of the nearby prisoners from sneaking out this way. The black dragon could probably kill the serpent, but it is too big to fit through the underwater tunnels (and the seawater dilutes the acid too much for it to corrode its way out).

#24: Crab, Giant. Conveniently showing up right after Sea Serpent, we’ll build out our ocean depths a bit more here. We’ll put the crabs a little closer to the core. They scavenge what the sea serpent doesn't eat itself, and are also occasionally consumed by it.

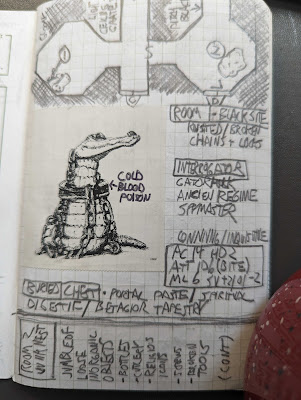

#18: Cat, Great. Rolling randomly for the sub-types once again we get… sabre-toothed tiger. Hell yeah. “Normally only found in Lost World regions.” OK. Maybe part of the purpose of this prison isn’t just to house criminals but also to preserve lost wildlife that no longer exists out in the world. I’m going to put the tiger near the nobles and the catfish – he’s been drawn to the fresh water and stalks the area nearby. There may be a supernatural zoo sub-theme we can explore with other entries.

#81: Nixie. Yeah, nixies are going to require some more dungeon infrastructure and background to explain. I’m beginning to think that entire prison is not just an island, but also overgrown and covered in natural growth on the top, including a large body of fresh water. The nixies were washed in here when the water eroded through the dungeon's ceiling and flooded several regions. The lake where the giant catfish lives is a terminus, but the nixies control the river flowing into it. They’d like to claim control of the lake, but the giant catfish is too big for them to deal with directly. They’ve probably charmed other humanoids, including a few of the noble’s retinue, and perhaps some others we haven’t placed yet.

#62: Insect Swarm. This could go anywhere, couldn’t it? We don’t need to explain why an insect swarm is in the prison, because insects just like to show up in places where they’re not supposed to be. I like how the OSE bestiary has such extensive procedures for encountering them. I’ll draw inspiration from one of those – the rules for escaping the swarm by “diving into water.” Putting them near the water gives the PCs an “out of the frying pan, into the fire” option that might send some of them into the arms of the nixies. I don’t want more bees, so we’re going to go with beetles instead. I think they’re actually plant-eaters and just want to consume the PCs clothes and other textiles, but adventurers won't know that, and their bites through the clothes still hurt!

#133: Wight. It’s interesting that OSE says these are “Corpses of humans or demihumans, possessed by malevolent spirits.” The 2014 5E Manual suggests they are more conventional undead, i.e., the evil spirit is animating the same body it occupied before death. The Monster Overhaul, my current go-to bestiary, emphasizes that “A Wight’s un-life is tied to an oath, a strong emotion, or the simple will to endure.” It has a nice random table of wight types. I rolled on it and got “Avenger.” Perhaps these are enforcers who swore an oath to the prison builders to hunt those who escaped their cells. The oath extends into un-life (oops) and they’re now doing this forever. I think the builders of this prison may be jerks. Per OSE, wights that drain someone of all levels create more wights, so these wights may be “recruiting” more hunters.

I don’t want a whole undead zone where they’re all clustered together, so I’m going to separate these guys from the mummy-zombie zone. We’ll place them in as-yet unexplored territory south of the ochre jelly zone. Mundane acid doesn’t harm them, so they’re safe from the jellies. Presumably they roam around looking for escapees, but their barracks are down there.

#92: Pixie. OSE treats pixies and sprites as separate things, and while the latter has a bit of a hook to it, pixies are quite boring. The Monster Overhaul lumps them together, but does include some extra flavor we can tap. They are often invisible and have a mercurial, forgetful nature. I like the idea that these invisible troublemakers were accidentally captured when some larger, more important prisoner was detained. That could place them almost anywhere, but the bigger the monster, the more plausible there presence here. I believe they are kind of Tinkerbelling or Jiminycricketing the dragon. The dragon probably finds them annoying, but hasn’t dissolved them yet, because their polymorph ability might come in handy at some point.

#36: Elemental. Picking randomly, we get fire elemental. OSE emphasizes they are summoned servants. Of the prison builder perhaps? I need more detail, so checking the Monster Overhaul, we get some excellent flavor and tables. The “who summoned this elemental?” table suggests tortoise tsar, a Monster Overhaul original, who has some fire-based powers, so fire elemental fits. The tortoise tsar isn’t part of my original conceit of using the OSE bestiary, but I can merge him with the dragon turtle entry. We’ll plan to revisit this situation when we roll up dragon turtle / tortoise tsar and figure out what is going on here.

#15: Caecilia. It’s OK, I had to look it up too. It’s an amphibian that looks like a snake or worm, although OSE’s are 30’ long. To take stock here, all of our monsters so far fit into one of the following categories:

- Prisoners or "zoo" animals

- Invasive species or other intruders

- Guardians or servants of the prison builders

- Creations of other creatures in the dungeon

I want to avoid putting all the monstrous animals in the second category. The prison should still feel prison-like, and not be completely overrun by creatures from outside. I think we’ll say these are prisoners, like our sabre-toothed tiger. Like the big cat, they’re extinct in the outside world (probably for the best – 30’ long, yikes!) but they live on here in the prison.

#11: Boar. As I said, there’s a lot of beasts in this bestiary. I’m going to tap the Monster Overhaul for inspiration again. It has a table for “local boar crimes,” which is too good to pass up. I rolled “ransacked a granary.” And I note that the Overhaul suggests boars are “as smart as most people.” I like the idea that the prison builders decided these 30-50 feral hogs were smart enough to stand trial for their crimes, just like people would. So they’re prisoners here, recently escaped from their cells, but still trapped within the larger prison. This could go in a sort of Silent Titans direction.

Next time: The World's Largest Rewrite: Floating Heads, Mother Fungus, Cellipedes

.jpg)

.jpg)