Some time ago, some friends-of-a-friend asked me about running D&D. They were reading the player’s handbook, and already talking about ancestry and class options. I asked several times if we could do a quick video call to talk about a potential game before they got too far along, but they weren’t in a hurry, and said they wanted to spend some more time with the book first. Unsurprisingly, communication trailed off and the putative game never coalesced.

One of the things they spent time thinking about – for this game that never came to be – was their backstories. I sometimes tell players that “backstory” is a banned word at my table. I am only kind of joking.

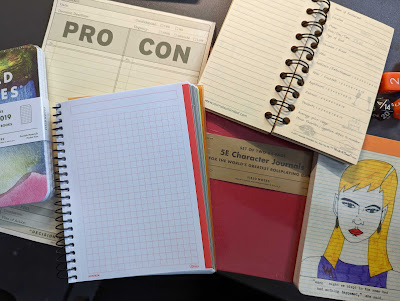

Players don’t appreciate that backstories are game-adjacent at best. They don’t support or advance at the table action. I’ve gone through several iterations of the Quantum Character Sheet because every hour of at-the-table action is worth a dozen hours of lonely fun spent crafting the perfect OC.

But players love backstories. Can we better incorporate them in the game itself? Other games I’ve played certainly do a better job. Let’s consider some approaches and hacks for D&D.

Not the DM’s Job

Modern D&D 5E play culture carries an unspoken assumption that the players create backstories and then feed them to the DM – potentially with secret or unresolved information. The onus is on the DM to incorporate disparate backstories into the game.

This can be helpful. And good DMs can use these backstories as fuel for session planning. But it can also create a lot of extra work; strain or distort the game’s tone; or create friction between different players’ very different ideas. Doubly so if the DM runs for a large group, or an open table.

So instead, perhaps players with backstories have to find their own way to introduce them into action at the table. Your wizard actually dropped out of magic school? Think of a way to reveal it to the other PCs. Your character is the last survivor of a clan of fey-touched warriors? Find a way to make the other PCs recognize and remember that information. It’s your job, not the DM’s.

Level Up Rewards

This is simple. Every time you level up, you flash back to a scene from your backstory. The player has broad discretion to set the scene, as long as it doesn’t contradict anything that has happened in the present. Bonus points if the player can tie the nature of the flashback to recent in-game events, or the abilities they’re gaining with level advancement.

This works if the characters view backstory as a reward for advancing. The drawback with this system is its more conspicuous if the characters who don’t care about backstories opt out.

Q&A Time

It is classic DM advice that you can learn a lot by asking the player questions about the character's history. “Has Thogdar ever shorn a sheep before?” The player knows – and knows that the DM knows – that this has never come up in a session. We also both know that it's not something the player thought about as part of any backstory planning. Without ever saying the b-word, we have invited them to create backstory, and in a way that could reveal something about their character that even they didn’t know.

Diegetic Objects

We take it for granted that many things in the game world can be turned into game objects. Spells and abilities can be encapsulated in magic items. A wizard reaching 5th level and learning fireball is, mechanically, not very different from acquiring a wand that allows the casting of the same spell.

So with that in mind, what if chunks of backstory are things within the game? This can be very literal – the characters have magical amnesia, and literally recover McGuffins that restore their memories. Or it can be a bit more figurative. The fey warrior who finds the lost family signet ring and establishes their lineage unlocks a slab of backstory. You want players to care about treasure? Bake their precious backstory into treasure, and they will care.